In December 2023, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began implementing new cybersecurity disclosure rules, which effectively introduced new reporting requirements for publicly traded companies. The rule, formally known as the "Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance and Incident Disclosure by Public Companies," began requiring companies to submit additional information related to cybersecurity preparedness.

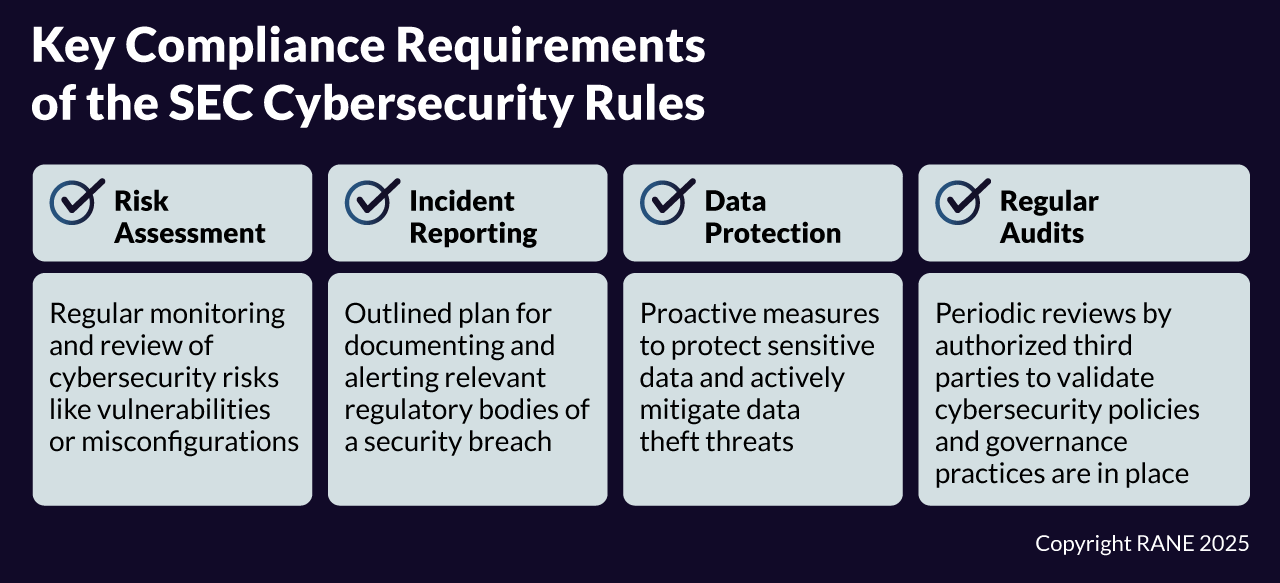

In particular, the new rules began requiring publicly-traded companies to begin adding additional information to two pre-existing SEC disclosure forms: the annual 10-K form and the 8-K periodic disclosure form. Under the new rules, companies are mandated to include annual descriptions of their internal corporate cyber governance and risk management policies in the 10-K form, including how the board of directors plays an oversight role in cybersecurity. Companies also must now be prepared to submit periodic 8-K forms – previously reserved for large-scale moves like a change in company leadership, a merger or acquisition or other kinds of major reorganization – to publicly disclose when a major "material" cyber incident occurs that could impact shareholders or customers within four days. Companies were encouraged to interpret materiality broadly and consider variables such as whether the incident jeopardized the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of internal systems and data.

While some data privacy advocates welcomed the SEC's more aggressive approach to cybersecurity requirements, many companies expressed significant apprehension around the ambiguity of some of the new rules' stipulations, including the concept of materiality and the short 96-hour reporting period for material cyber incidents. Some cybersecurity experts also expressed concerns that providing explicit information on a company's cyber defense measures could inform potential bad actors on specifically how they can discover and breach vulnerabilities.

In the most recent example of company pushback around the SEC's cybersecurity rules, several prominent members of the U.S. banking industry – including the American Bankers Association and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association – published a petition on May 22, asking the Commission to rescind the rule. The petition argues that the rules add more requirements to "an already complex list of reporting and disclosure obligations that financial institutions and other critical infrastructure sector companies must follow." The petition also claims that the rules introduce confusing compliance requirements for both companies and their investors, creating the risk for companies to disclose information even while incidents are ongoing or expose critical information that financially motivated cybercriminals like ransomware groups can exploit.

Currently, the SEC has not indicated that it is imminently planning to rescind the current cybersecurity rules for publicly traded companies. That being said, the Commission's new Chairman, Paul Atkins, appointed by then president-elect Donald Trump in December 2024, is known for supporting a hands-off approach and had promised to pursue a range of deregulatory initiatives. While rescinding the rule entirely would be more challenging, as it would require Atkins to propose new rules in its place in a time-consuming process, he may look to undercut the rule's enforcement and/or scope. In an example of how Atkins' supports less regulation on cybersecurity, the SEC scrapped proposed cybersecurity rules for investment advisers and companies participating in securities markets on June 16 that the previous outgoing administration had drafted.

If the SEC does lessen its enforcement of its cybersecurity rules, companies will face fewer noncompliance risks that could result from incomplete disclosure, including financial penalties and audits or investigations. On the other hand, however, some companies may subsequently invest fewer resources or oversight into internal cybersecurity activities, elevating the risk for some entities to be more vulnerable to malicious intrusion. Weaker enforcement could also lead to less clarity between companies, shareholders or customers around cyber incidents that could imperil the organization's internal data and financial assets.